ArchiTravel interviews the architect Nabil Gholam.

Interview by : Christianna Tsigkou

Christianna Tsigkou: What is the importance of architectural tourism?

Nabil Gholam: Besides the positive elements of tourism in general which can always be beneficial to a country or a city especially of the second or third world, it has a potential to make a difference and highlight architecture as a key element. As we like to believe as architects that we can make a difference, this would be a sort of a direct way. Having lived in Barcelona for a very long time I could really see firsthand the impact that good architecture and planning had on the tourism of the city. A large percentage of the people, more than any other city I know, who would come to Barcelona, were at least partially interested in its architecture from Gaudi, all the way down to the more contemporary and recent. You have a particular group of people, often students or academics, that travel here as tourists and also get themselves excellent exposure to the quality of the architectural works in the city. I’m definitely a supporter of architectural tourism, which architect wouldn’t be?

C.T.: What is the importance of traveling, especially for architects and humans in general?

N.G.: Well, I will talk mainly for architects as we were having a discussion earlier with a colleague of mine. For example, in Lebanon, Lebanese people tend to travel quite a lot for such a small country, but it still is not enough. The more you travel, the more exposure you get and the more exposure you get, the more chances you have to better understand the problems of today and have a sense of perspective, perhaps a vision that is other than one that was developed in the place you were born or live or like. I have always enjoyed some of the advantages of provincialism in the fact that each place has its own charm and character, but at the same time it’s hard to say that beyond the real vernacular (which often is excellent work in response to real needs), provincialism can contribute in any way in creating good architecture in most situations. There are exceptions of course. So, in that sense I would say definitely travel as much as you can. Do not limit yourself to one place. That’s how architecture evolves too.

C.T.: What is the role of architecture as a destination and the added value that it creates within a city?

N.G.: Architecture as a magnet to attract visitor is second to its primary role in the life of its local users, however, it is a kind of virtuous circle, a win-win situation where good pertinent architecture can do both and start generating notoriety and business for the city it is located in.

C.T.: What is the importance of architectural events worldwide? What are the profits for a city holding such kind of major events?

N.G.: Clearly, to me it’s great exposure, again. Following the same logic, you come to see lots of different things done by different people in different ways. But most of these often contemplate the same problems that apply to a building, neighborhood or a city. You can see that they work in a certain way in Singapore, in Tokyo. By comparing and contrasting you can find out more about contributing and how to do it. There is something to learn about another culture’s approach to a given problem. So, in that sense, exposure is key. As for Barcelona, I can see that’s not the case very much anymore. It certainly adds one little flower to their bouquet, but Barcelona is already very established as a destination for all sorts of events at this point, and as the mayor very bluntly said in his speech, they have already paid their dues. It adds in the sense that, you would send your friends to Barcelona, because they’ve all heard of it, and more visitors would keep coming that way.

C.T.: You have created the architectural office “Nabil Gholam Architects”. Your office not only finds simple solutions to complex problems and breathes life into projects, but believes in design as the best way to creating lasting real architecture.

Lebanon is a country with great history. Designing a modern building within this context is a complex procedure. Is critical regionalism an approach to your architecture?

N.G.: We’re bad with our neighbors. Although we probably have a lot of common philosophies. Our country was torn by war, so you feel that you have to do something that has some relevance and pertinence to the place, to mending its divisions. The way things are being done differs a lot from one person to another, depending where you are and how people live. That doesn’t mean that you cannot learn something in Ireland that you can mix with something you found in Kyoto and that those elements might end up bridging together into an unexpected solution, that would turn out to be fantastic and totally fantastic in a Mediterranean location.

I can give you an example. Living in Spain has been very interesting, because Andalucía was obviously under Arab occupation and Muslim occupation for about 800 years. So I find there some things that the Arabs have lost or abandoned along the way that make a lot more sense than some of the evolutions of the same things in our region or even their disappearance. You might think that they are much more in line with the history and the culture of this particular world. When you see modern Cordoba, some say “Dubai”, while Dubai might have more to do with something they tried to mimic from Las Vegas or elsewhere. I’m using clichés to say that, yes, in that sense it is important to have a critical eye on your region to see how you can offer enrichment, but still think of it more than just from a fashionable cosmetic angle, something that would gain attraction and publicity. Otherwise it will be looked down by future generations and add little meaning. How will it look then, I think is a difficult question and an interesting one.

C.T.: How would you characterize modern architecture in Lebanon?

N.G.: Well, it’s trying to sort itself out of the confusion caused by a huge gap followed by huge progress. Lebanese architecture was somewhat of a very interesting mix of local, oriental, Mediterranean and even sometimes idealistic designs, but always with a window open to the west. And then the civil war came in 1975 and put an end to that continuum. During the war the people built as well as they could, they built much more than you would think. A lot of buildings were torn down due to the war and a lot more very unfortunate ones were built in survival or for greed, or sometimes in a combination of both. So, they disfigured a lot of our landscape. Today, after ten years of what I would say is a period of right after the end of the war in 1992 until the late ‘90s early ‘00s, you could see how people were still almost shocked of coming out of the war and had a tendency to repeat what they did during the war in terms of building models, what they called, strangely enough, “Classic Buildings”, a confused and conservative version of what had happened before yet disconnected somehow from what was going on elsewhere. Recently, I would say the last 3 to 5 years, a climax has begun in modern architecture.

Most developers are turning to more contemporary solutions looking for good architecture as another source of success and profit. Maybe they like it too, sometimes hard to tell. But today definitely things have changed and Lebanon’s contemporary panorama of architecture is very vibrant and vital. A lot is happening again. I urge you to go and visit. Some of it is quite disorientated still and the fact that the laws are antiquated is frustrating, but at the same time there are some freedoms that we have lost in the west.

C.T.: Ngª’s team is committed to a set of core values focused on delivering quality design maintaining broader social, cultural, economic and ecological sensitivity. How do you achieve these goals in your designs?

N.G.: We’re very pragmatic. We try to work on a day to day basis and we try to use a sort of example-driven system rather than a dogmatic system, where you go through dogmas and philosophies. We believe that we can take a lot from common sense and just keep building on what you know and adding to it, experimenting. And when you are experimenting you try to do as little damage as possible, because sometimes you can overshoot in our business while trying to do something interesting. So, in that sense, we try to have a certain modesty to in our work, or we try to question our motives. We don’t like to talk a lot about it and try to explain. I think that buildings have to speak for themselves and the best way is to visit the building or use it, live in it and see for yourself if it is what you wanted and more, how it surprises you, what it adds to your day…

C.T.: In recent years attention turns to green urban regeneration. Do you think that it is imperative for the city or is it just a new fashion with economic outcomes and covertly interests?

N.G.: There’s always a part of it that’s fashion. Obviously, some of the fashion has some benefits because it gets people to turn to it and at least become aware and consider it. The part that I find quite comical, if not a bit tragic, is that there are a lot of superficial elements, that practices feel need to be “slapped on” on a given work, like sounds bits, as they feel these are required. That is a bit sad. Because it seems that the competition-driven system and publications have become quite obsessed; if you don’t offer that, you’re not going to be looked at. People should take it more in depth. We did a house sixteen years ago in Lebanon, our first house, that was entirely environmental, at a time when nobody was really talking about that; it used very little electricity, no heating, no cooling, collected the rain water, was simply well oriented, but we were afraid it would scare the client. Because at the time when we told a client that this was an environmental approach, he said “Are you mad? We don’t want to spend on that!” So we sort of were “green” from the start, but a bit in the closet about it. And when it was built, they couldn’t believe their eyes and they were happy and we were happy, and laughed that we had done it almost in hiding.

The house uses no heating or air conditioning throughout the year since, and has been generating great climactic comfort and economy together. Now clients come to you asking for it. Recently we finished designing a building and the construction started, it’s a tall tower in Beirut whose entire energy system will be solar. This is common elsewhere, but in Lebanon it’s the first, yet we have over 300 days of sun a year. And that is interesting because people there tend to work by example, in the sense that they like to imitate and acquire what they thing is best. That will generate positivity and more people will do it and eventually on the long term we will have less pollution and use less fuels. It’s also nice because sun is free energy, and with the rising cost of oil, people are starting to listen more in Middle East. But beyond that, at the level of the city and the country, I feel that in Lebanon there is not very much new real “green” yet. We’re often busy dealing with somewhat more regional problems.

C.T.: At the end, can you please provide your personal proposal for 10 buildings which you think as the most important worldwide that someone must visit anyway?

- The Agrippa Pantheon in Rome

- Hagia Sophia in Istanbul

- The Mezquita de Cordoba

- The Alhambra in Grenada

- Mies van der Rohe’s Pavillon in Barcelona

- The Chrysler Building in New York

- The HSBC Building in Honk Kong by Norman Foster

- Menil Collection Museum in Houston, Texas by Renzo Piano

- National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladeshby Louis Kahn

- An inhabited patio house in Morocco or Andalusia, any good one

Faetured image © Marco Pinarelli

More on : Nabil Gholam

About this Author : Christianna Tsigkou

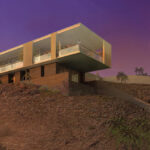

Work of Nabil Gholam

Interview Backstage